We now know that 28-year old fishing observer Emmanuel Essien was actively taking actions against vessels engaged in illegal fishing practices before he vanished onboard a Chinese-owned trawler called Meng Xin 15 on July 5th 2019. In his report on the penultimate vessel he worked on, dated 24 June, he wrote: “I humbly plead with the police to investigate further”.

The job of a vessel observer is to ensure that licenced vessels comply with the local laws. In Ghana, an observer’s allegations if proven to be true could result in a minimum US$1m fine.

“I don’t believe government and the authorities valued the work my brother was doing,” said James, the elder brother of Emmanuel. “If they did, they would attach some seriousness and urgency to the investigation. We know nothing. We don’t understand how it can take so long.

“Bribery and corruption are rife in the sector, with observers forced to accept bribes from Chinese officers to stop them from reporting on illegal activities,” said Steve Trent, Director of Environmental Justice Foundation (EJF).

A new EJF report estimates that Ghana could generate between US$14-24million annually from its trawl sector by way of fishing licence fees and fisheries-related infringements, but fisheries resources are being sold-off for negligible returns.

A three-month investigation by Gideon Sarpong and Elfredah Kevin-Alerechi – based on interviews with dozens of fishery experts, court records and company and financial documents – has established a hidden network of Chinese control and ownership of many industrial fishing vessels operating in Ghanaian waters in contravention of local laws.

The investigation also shows that these Chinese companies commonly operate through ‘front’ companies to obtain fishing licences – and with very minimal action from regulatory bodies. The investigation established that in contravention of the Ghana’s Fisheries Management Plan, the Fisheries Commission in 2019 granted three fishing licences to Shandong Zhonglu Oceanic Fisheries Co. Ltd. – a publicly traded Chinese company that made millions of dollars in profit from its operations in Ghana during 2018.

Transhipment activities in Ghana and Nigeria

At an open shed along the coast of Elmina, one can hear the chatter of resting fishers dominated by the painted hulls of newly-returned pirogues strewn with flags and washing. Some of these canoes are also seen stacked with slabs of mixed frozen fish at the port.

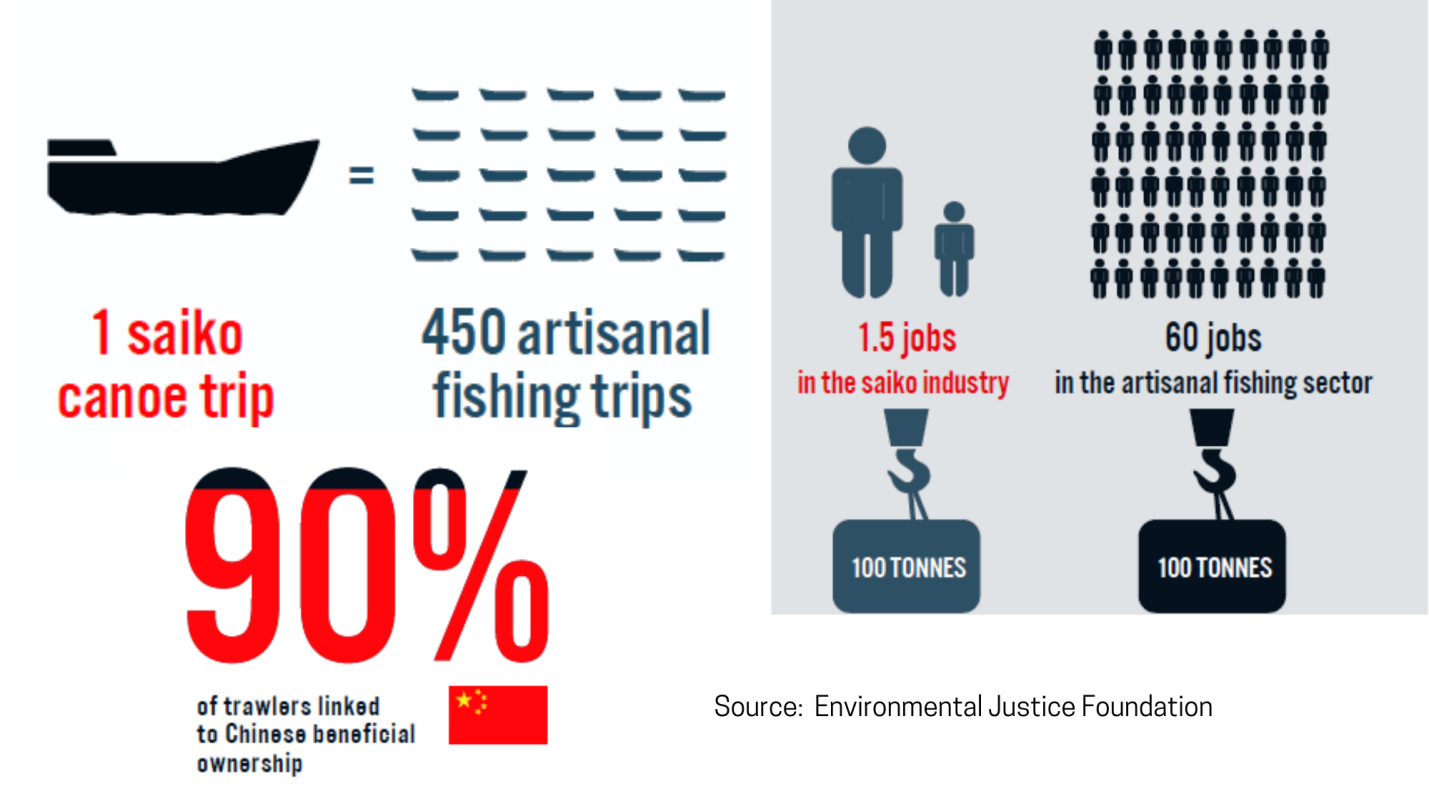

Francis Adam, President of the Central Region Fishermen, explains why frozen fish can be found in some canoes: “Industrial fishing trawlers licenced to harvest demersal (bottom-dwelling) species deliberately target the staple catch of artisanal fishers, the small pelagics, and sell such fish back to the local coastal communities at a profit”. This process is known as transhipment or ‘Saiko’ in Ghana.

Transhipment is a severely destructive form of illegal fishing according to Ghana’s Fisheries Act 625 of 2002, which expressively prohibits the practice. The law seems to be of little consequence, as this very profitable venture takes place openly at the Elmina harbour.

Francis bemoaned the decreasing rate of catches by artisanal fishers in Ghana, and directly blamed ‘Saiko’” for the drop. “I have been in the fishing business for over three decades, but the last decade has been most challenging due to the dramatic reduction in our catches as a result of Saiko,” he said.

Although fishing efforts by the artisanal fleet has been increasing, catches of small pelagics fell to only 19,608 metric tonnes in 2016 – a sharp decline from the peak in reported landings of 138,955 metric tonnes recorded in 1996, the Fisheries Scientific and Technical Working Group (STWG) has estimated. The report also warned that Ghana’s pelagic fish stock is in imminent danger and could collapse completely by the close of 2020.

An average saiko canoe lands in a single trip the equivalent of approximately 450 artisanal fishing trips. “This is a major threat to over 100,000 artisanal fishers in Ghana who depend on fishing for their livelihoods and the long-term viability of Ghana’s fisheries,” says Dr. Isaac Okyere, a researcher at the University of Cape Coast. He added: “It has now become obvious that the small pelagic fish they catch is no more a by-catch. The by-catch has become the target and the demarsal fish has become the by-catch.”

“A fish population is just like a human population; if we start killing our children, what will become of society. It is a whole lot of illegality; from the net they [Chinese Trawlers] are using, from where they are fishing, from the species they are catching and from their sizes,” says Dr. Okyere.

Meanwhile, in Nigeria the situation is not entirely different. Foreign-owned vessels in connivance with some local fishermen and security officials engage in transhipment activities despite prohibition by the Sea Fisheries Act, says Mr. Monwon, a local fisher.

Transhipment activities by Chinese-owned trawlers are considered a major problem at Oyorokoto, in the Niger Delta region. Mr. Monwon, recounted how he was threatened at sea after confronting a Chinese-manned vessel; and blamed transhipment activities for the dwindling catch and economic hardship facing many residents of Oyorokoto who depend on artisanal fishing for their livelihoods.

“After they have finished fishing, we hardly see fish to catch,” said Mr. Monwom, pointing to a fishing vessel at a far distance.

Head of artisanal fishermen in Bonny, Promise Bristol, also shared similar sentiments: “Foreign trawlers connive with security agents to attack local fishermen who rebel against their illegal activities”.

Could it be that Emmanuel’s dedication to fighting illegal trawler activities might have unsettled his Chinese crew and resulted in his disappearance?

James, Emmanuel’s brother, believes there was foul play: “I suspect there was a coordinated attempt to take him out. He was going to write a report. Perhaps there was a disagreement. Perhaps the Chinese didn’t like it.”

It has been over a year since Emmanuel went missing, and checks at the Attorney General’s office in Ghana suggest there has not been any official report or prosecution by the state.

In the same month Emmanuel went missing, an industrial Chinese trawler – Lu Rong Yuan Yu 956 (AF 756), fronted by Gyinam Fisheries Limited in Ghana – was arrested and fined US$1m for engaging in illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing.

The Lu Rong Yuan Yu 956 (AF 756) – in spite of failing to pay the US$1m fine in October 2019 – was re-licenced to fish again; and in May 2020 was re-arrested for almost identical illegal fishing offences.

“Opaque ownership arrangements in Ghana’s fishing industry are a root-cause of governance and management failures in the sector, and are certainly impeding effective prosecutions for fisheries offences. Prosecutions fail to target the beneficial owners – often a much larger entity with a controlling interest in the vessel – to ensure sanctions imposed are proportionate and have a deterrent effect,” says Trent.

Marine Police Director, DCOP Iddi Seidu whose unit led the arrest, admitted that “strict enforcement and application of the fisheries laws” is critical in dealing with this menace.

Hidden Chinese fleet in West Africa

So far, several petitions by Ghana National Canoe Fishermen Council (GNCFC) to the Fisheries Commission and president of Ghana have failed to curb this practice.

Our investigation uncovered that in 2019 fishing licences were granted to three Chinese vessels in contravention of government’s own Fisheries Management Plan, which states 48 trawlers are the most that the fishery sector can sustain, and also in violation of a government moratorium dating from 2012.

As at 2017, the number of licenced vessels in Ghana stood at 76. In that same year, the Fisheries Ministry halted publication of the vessel licence registry and ownership information: a step many experts described as a significant blow to transparency and accountability.

Shandong Zhonglu Oceanic Fisheries Co. Ltd. is a publicly traded Chinese company that has admitted to using a Special Purpose Vehicle via an operational lease to exert control over a number of Ghanaian-registered companies. The companies – Laif Fisheries Company Limited, Yaw Addo Fisheries Company Limited, Zhong Gha Foods Company Limited and Africa Star Fisheries Limited – were described as “significant foreign operating entities” in its 2018/9 annual report.

The company, in its annual report and on its website, also admitted to receiving fishing licences from officials in Ghana for three fishing vessels in April 2019. The company financials showed that it generated significant returns from its operations in Ghana. In 2018 alone, it made over US$4.5m in profits from its fishing establishments within country.

“The Ghanaian law expressly forbids foreign ownership of industrial trawl vessels operating under the Ghanaian flag: both in terms of ownership on paper and, crucially, in terms of those who profit from the vessel – known as the ‘beneficial owners’,” says Trent.

“The new 2019 Companies Act (Act 992) clarifies the definition of a beneficial owner, showing clearly that the way Chinese fishing corporations are using Ghanaian front-companies is illegal,” he adds.

In a strongly-worded letter to the Director of the Fisheries Commission in Ghana in May 2020, the GNCFC argued that they are “firmly opposed” to any decision to issue licence for new vessels to fish in Ghana.

Ghanaian subsidiary companies acquire licences directly from the Ministry of Agriculture “through some opaque and phony arrangements”, while the vessels are “manned by Chinese owners”: this is illegal, says Kofi Agbogah, Director of the Ghanaian fisheries and coastal governance NGO, Hen Mpoano.

“With powerful interests at play, it will require political commitment at the highest levels of government to oversee reforms and ensure progress is not derailed by political lobbying or interference,” Trent recommends.

The Director of Fisheries Commission in Ghana, Arthur Dadzie, failed to respond to several requests to be interviewed for this report.

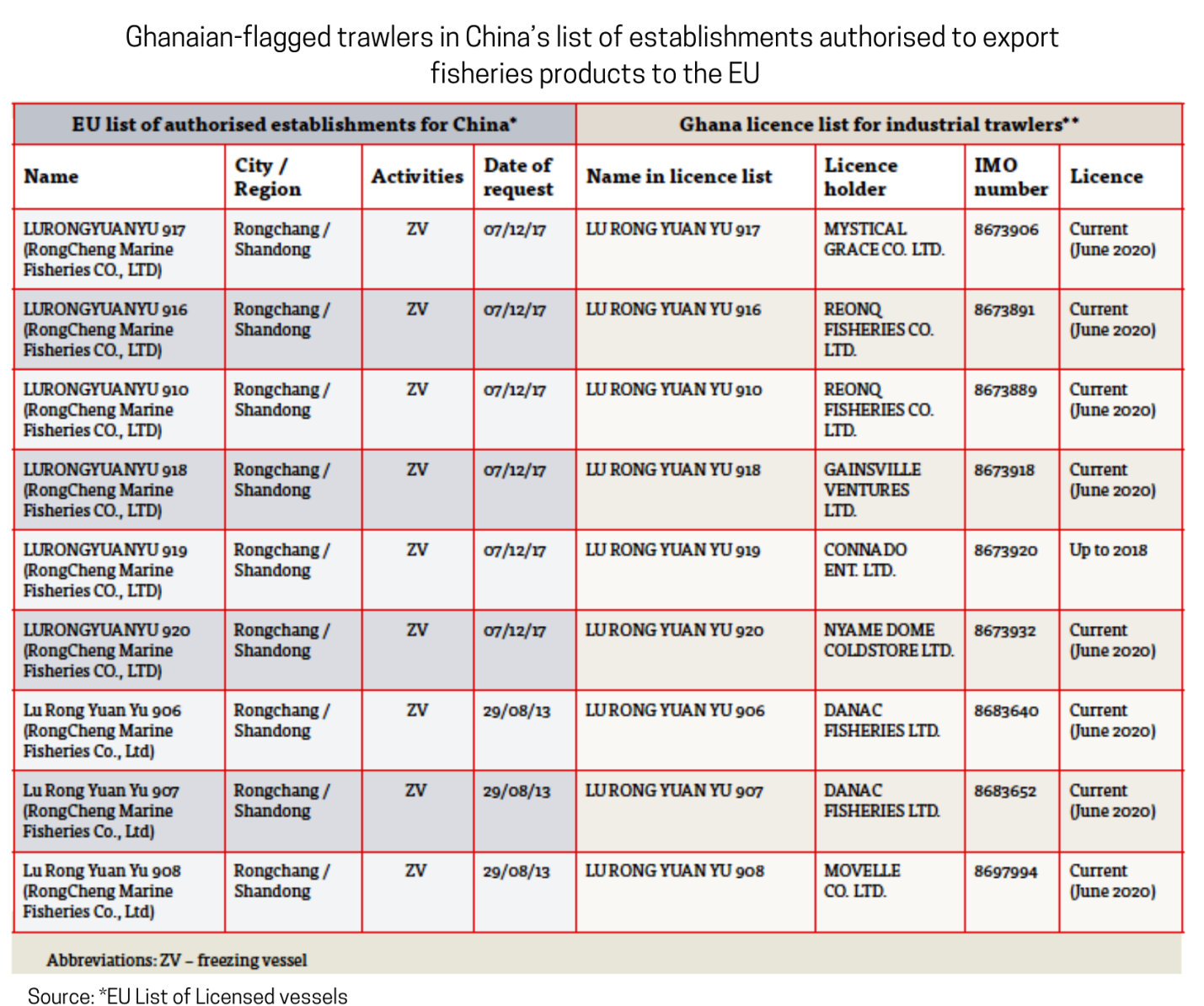

Our investigation also uncovered that nine vessels owned and controlled by Chinese companies have set up front-companies to conceal their influence and circumvent local laws in Ghana.

These nine Ghanaian-flagged trawlers authorised to export catches to the European Union also appeared on the Chinese list of establishments authorised to also export fisheries products to the EU.

A 2019 World Bank report highlighted the Ghanaian government’s “weak commitment to reducing the industrial segment’s fishing capacity”. The report further noted that the government is “highly influenced by forces within the industrial segment”, and raised concerns that foreign-owned vessels being allowed to register in Ghana under beneficial ownership arrangements were not being investigated.

“The European Commission must use all tools foreseen under the EU IUU Regulation if it is demonstrated that Ghana has failed to discharge its duties to effectively address IUU fishing under international law,” says Trent.

Illegal and destructive practices by foreign-owned trawlers are draining the Ghanaian economy of US$50m a year according to EJF.

Meanwhile in Nigeria, many marine and coastal ecosystems are close to collapse due to IUU fishing, reveals Prof. Chioma Nzeh at the Department of Zoology, University of Ilorin.

Annually, Nigeria loses as much as US$70million to IUU activities, Nigeria Navy reports in a 2018 estimated.

Many of these Chinese fishing vessels do not have fishing licences, and they fish as far as four nautical miles – depriving local fishers of their daily catch. Four Chinese fishing vessels were arrested by the Nigerian Navy in August 2017 while fishing within the Non-Trawling Zone (2-6 nautical miles).

The Nigerian government should do the needful to “come up with effective laws, and there must be proper monitoring by officials of the federal Department of fisheries (FDF)”, said Nene Jamabo, Rivers State Chairman and Fisheries Association of Nigeria.

However, in Ghana, Emmanuel’s family is no closer to knowing the truth about what happened to their son on that fateful day. Despite an investigation that showed the Meng Xin 15 belongs to a Chinese state-owned enterprise, Dalian Meng Xin Ocean Fisheries, no action has been taken so far by the Ghanaian government against the vessel owners and its crew.

“My mother keeps calling me, saying: ‘have you heard from the police? Tell them to bring my son’,” says James.

Political Inaction and weak penalty system

All of these revelations raise important questions about why officials in Ghana and Nigeria have failed to take any urgent action to deal with the perpetrators and beneficiaries of illegal fishing practices.

Kofi Agbogah and Francis Adam, who have been at the forefront of activism against IUU, directly blamed powerful political players who encourage these licencing arrangements and illegal fishing practices.

“A number of ‘politically exposed persons’ (a term used in the 2019 Companies Act) hold directorships and shares in local companies which hold the licences for trawl vessels operating in Ghana,” said Trent. “We have heard allegations of such individuals lobbying for the registration of new vessels and for enforcement proceedings to be dropped, sanctions reduced or licences reinstated.”

From 2007 to 2015, 199 fishing vessels were arrested for various fishery offences in Ghana according to a USAID report. The report also noted that “some fines were not paid in full, and in some cases the Minister of Fisheries accepted less the amount imposed”.

For a country with close to 25 percent of its population living below the poverty line, “Ghana’s valuable fisheries resources are being sold off for negligible returns to foreign operators in breach of the law,” says Trent.

The World Bank has estimated that incomes of artisanal fishers in West Africa have reduced by 40 percent over the past decade, plunging many fishers into abject poverty.

Ghana’s Fisheries Minister, Elizabeth Afoley Quaye – who declined a request for an interview, came under intense criticism after she backed illegal transshipment activities in March 2020. She has since revised her position, but has done “very little to curb the practice” according to local fishers.

EU and International Action

The European Union Council imposed a three-year ban on Ghana in 2012 for failure to monitor fishing fleets, neglecting to impose sanctions on illegal fishing operators, and failing to develop robust fisheries laws.

As a market for seafood caught by the Ghana-flagged trawl fleet, Francis Adam – an advocate against IUU, is of the view that “the EU may be the final hope Ghana and Nigeria may have to restore some order in the fisheries sector”.

Francis is convinced that a recent threat of a ban by the EU could be the jolt needed for reforms within the fisheries sector of Ghana.

But with the EU embroiled in contentious BREXIT negotiations, Dirk Siebels – a member of Global Initiative Against Transnational Crime, believes that officials in Ghana and Nigeria need the “political will, coupled with transparent processes” to curb transshipment and illegal trawler activities.

Meanwhile, EJF has recommended that both Ghana and Chinese governments “must collaborate” to ensure that the “perpetrators and beneficiaries of illegal fishing are identified and held to account in a transparent processes”.

For Dr. Okyere, the solution must be a radical one: “If we truly are serious about stopping the destructive nature of transshipment, then all industrial trawling in our waters must be halted entirely until significant reforms are done”.

Reporting and writing by Gideon Sarpong (Ghana) and Elfreda Kevin-Alerechi (Nigeria).

This article was developed with the support of the Money Trail Project (www.money-trail.org).

SOURCE: thebftonline.com